Japanese-American prison camp survivor tells her story

When sharing her experience in Topaz during World War II, Alice Hirai forgoes tame words like “relocation” and prefers to refer to it as a “prison camp.”

“What happened to the Japanese Americans — and this is not said enough — is that this was the worst civil rights violation in the history of the United States,” Hirai said.

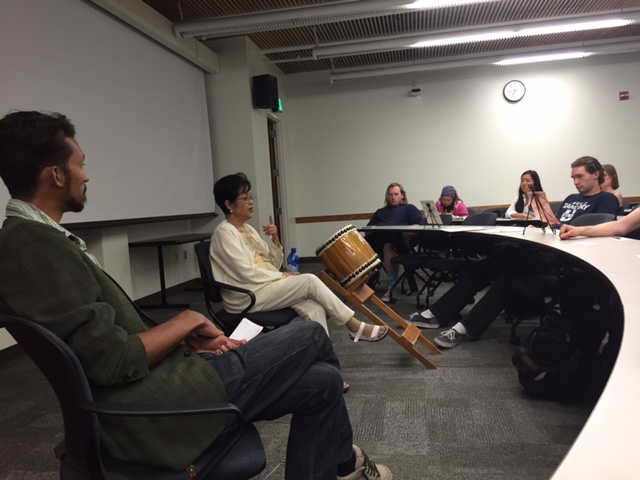

Out of 126,000 prisoners, most have died or become too ill to tell their experience firsthand. Because of this, Hirai said she will share her story with anyone who will listen. Hirai spoke at Utah State University on Friday, April 22.

Hirai was only 3 years old when she and her family were taken from their homes and sent to the Topaz War Relocation Center near Delta, Utah. Though she was young at the time, Hirai has interviewed former prisoners and historians to gain context.

Even before the attack on Pearl Harbor, there was discrimination against the Japanese in America, Hirai said. After Pearl Harbor, leaders in the Japanese American communities, who were monitored by the FBI without their knowledge, were taken from their families and imprisoned for the entirety of the war. Shortly after, anyone of Japanese descent was decreed to leave their home and relocate. Any items they didn’t collect after two weeks were lost, Hirai said.

Wanting to keep their dignity, Japanese Americans showed up on moving day wearing their Sunday best. They also wore dog tags with preassigned numbers.

Hirai and her family were sent to a temporary location, Tanforan racetrack. They lived in horse stalls. Hirai’s grandmother was diagnosed with terminal stomach cancer. Two men drove her to Tanforan and left her on the side of the road; she was too weak to move. She died in a hospital a few days later. This was part of the reason why Hirai became a registered nurse later in life.

“I want to do a better job as a nurse and never treat a patient like this,” she said.

When prisoners arrived in Topaz, they had barracks to call home. There was no insulation. Each barrack was 14 by 20 feet and housed six families, which made privacy impossible. Other than community toilets and showers, there were no utilities. However, prisoners wanted to make life in the camp as comfortable as possible.

“They were doing all they could to make their lives better within the camp,” said Atsuko Neely, a Japanese professor at USU who has collected stories from survivors. “They had their own initiative to work so that the camp life was improving.”

While there were guards, most prisoners were compliant. Japanese Americans wanted to prove they were loyal to America, Hirai said. With time, they were trusted and even allowed to leave the camp from time to time. This was, in part, because they didn’t have anywhere to go.

After the war the prisoners were released, and most did not have a home to go return to. The generation before Hirai wanted to try to forget what had happened and move on. For a long time, there was no oral or written history of what happened, Hirai said.

Discrimination against Japanese Americans remained, but Hirai is grateful she stayed in Utah.

“The [Church of Jesus Christ and Latter-day Saints] community welcomed us,” Hirai said. “The LDS, because they were persecuted, treated us really well.”

Hirai noted parallels between the culture that led to the imprisonment of her family and today. She recalled a recent trip to the grocery store, where she overheard a cashier and a customer saying they don’t like Muslims.

“If I had time, I would have stopped that conversation because that’s the kind of person I am,” Hirai said. “I wanted to say, ‘If you’re saying you hate Muslims, that means you don’t like me. I’m Japanese. That’s why I got sent to prison camps, because they were saying the same thing you’re saying right now.'”

Hirai encouraged attendees to vote. That way, no group of people has to have their civil rights taken away with the stroke of a pen like she did.

— whitney.howard@aggiemail.usu.edu