What is that green laser in the sky?

Strolling across campus on a cloudless night, students can look up and see a bright green line pierce the sky. The “green beam,” as it is referred to by locals, is one of the many things that makes Utah State University unique.

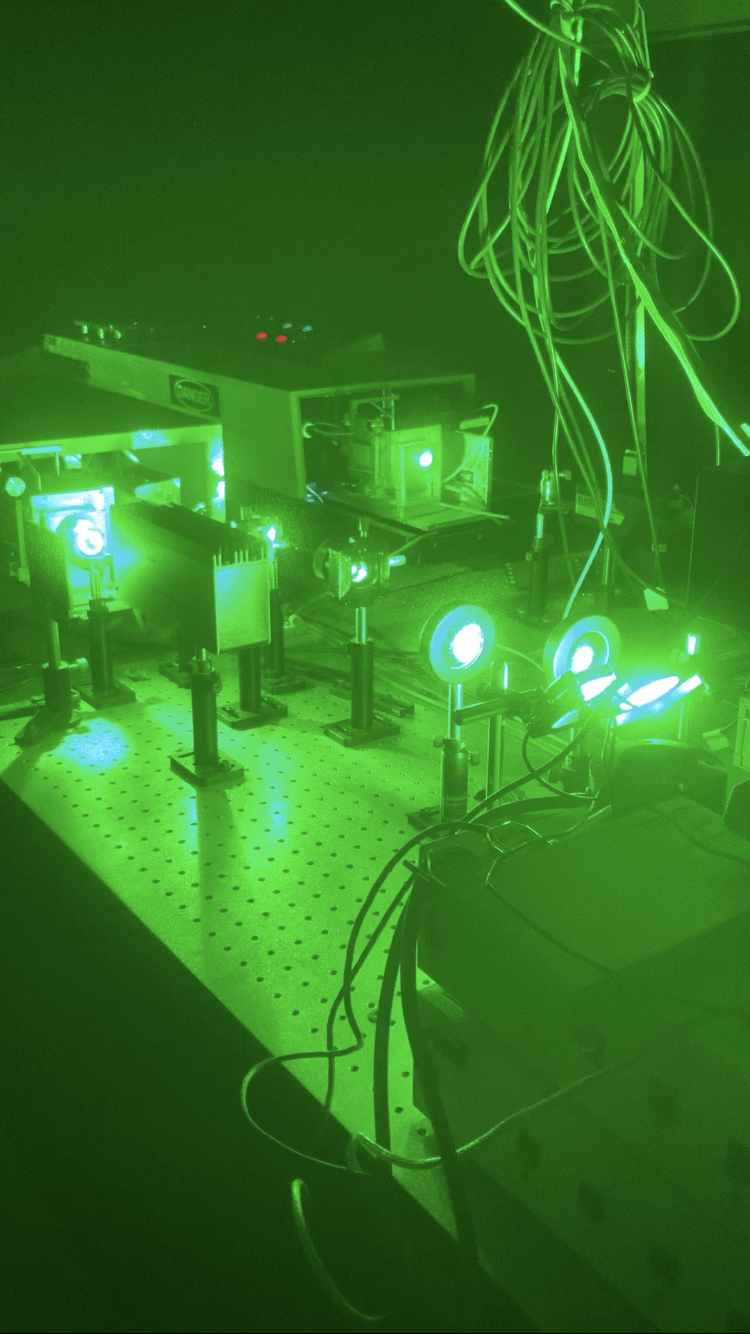

The laser is used to collect data about the atmosphere’s temperature, contents and sometimes density by scattering the light of nitrogen, oxygen, methane and other elements. Some of that scattered light comes back and hits a large telescope with multiple mirrors that accumulate the light coming back from the atoms.

Jan Sojka, head of USU’s physics department, said they are producing an altitude profile of reflected light from the atoms and molecules.

“It’s just like a radar system,” Sojka said. “The radar system sends out a pulse of radio waves. It hits the airplane and comes back, and you measure the time it took the radio waves to go and come back, and then you know the distance.”

A significant part of the project is funded by The National Science Foundation and NASA.

“NASA would like this knowledge and NSF would too — that means that the scientific community worldwide is interested,” Sojka said. “The Department of Defense also is always interested in these things.”

According to Sojka, working with the laser is a good way for students to gain valuable experience with industrial safety.

“The first thing that the students learn in this industrial, very intense laser system is how to safely work with these things,” Sojka said.

Sojka said the “green beam” is powerful enough to immediately ignite a piece of paper.

“It has four very large mirrors that collect the light, and that makes it one of the most powerful LiDAR systems in the world,” Sojka said.

LiDAR is a type of system that uses remote sensing with a quick-firing laser. The laser pulses are used to measure returned light.

Jonathan Price, a LiDAR observation and data analyst, recently took charge of the laser project. Since Vincent Wickwar’s death in Sept. of 2022, Price now leads the observatory. Price joined Wickwar’s research group as a postdoctoral fellow in Aug. of 2021.

“We send the beam up with what’s called elastic collision,” said Price. “I guess you could say it sort of bounces off the particles and reflects down to us.”

Price said the laser helps measure an area in the atmosphere that is typically hard to gather data on.

“This region we’re looking at — there’s not very many instruments that can look there,” Price said. “We can only operate at night.”

The laser can also only operate when there are minimal clouds in the sky.

“To give you a comparison, 30 kilometers — weather balloons typically go to that altitude,” Price said. “So, we start where the weather balloons end. And then at 100 kilometers is considered the edge of space.”

The atmosphere is separated into layers that can be identified by their temperature structures.

“Our science is trying to couple what is happening in the upper atmosphere to what is happening here below — where we are, in the troposphere — so that we can kind of understand how the sun is controlling the weather a little better,” Price said.

Aggie Figueredo, an undergraduate at USU, helps monitor the laser. Majoring in physics and computational mathematics, Figueredo said the correct frequency must be sent up for the results to come back.

“With electrons, you can send the right frequency that’ll give the other the amount of energy that it needs to bounce back and forth,” Figueredo said. “And certain molecules — when they’re together — indicate global warming.”

Figueredo said the laser has picked up other factors that point to global warming.

“Early 2000s, they started seeing an increase in the concentration of water and temperature,” Figueredo said. “It started getting more dry over time. So, Utah has always been dry, but it started losing more water. There’s also an increase in average temperature.”

While the team does not have enough information to indicate climate change with the laser, some signs point to global warming in the data.

“We might be able to see signatures in the data hinting at climate change,” Price said. “But we just don’t have enough of it — enough years of observation — to definitely pronounce climate change.”