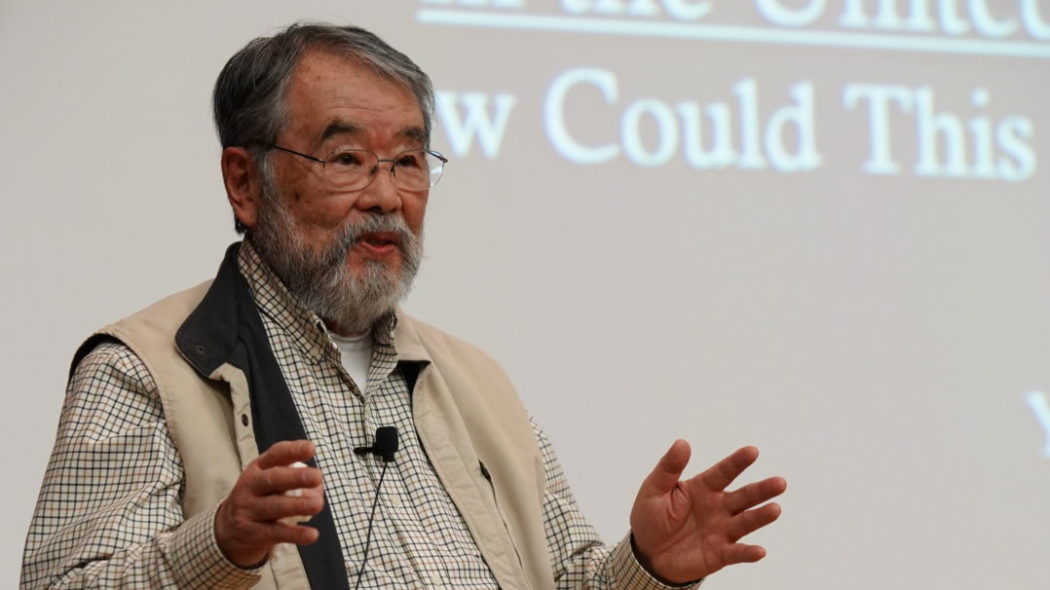

Alumnus forced into WWII internment camp speaks at USU

Yukio Shimomura graduated from Utah State University in 1965. In 2019, he is the last living member of his family to be detained in an internment camp during World War II.

Shimomura spoke to an audience at the Taggart Student Center on Wednesday about his life and his two and a half years “behind barbed wire.”

Shimomura was invited to speak by the USU Asian Student Association and USU Access and Diversity. He lived in Ogden from 1947 to 1962 after the war ended.

“I attended Lewis Junior High School in Ogden in 1947 when I first met Yukio,” said Jim Hurst while introducing his friend of over 70 years.

“Bob [Hazen] came up to me and asked if I had met Yukio. He told me that he is ‘one angry dude,’” Hurst said. “Well Bob was right because Yukio in that era of his life was a pretty angry young man because of how he was treated being a Japanese American.”

Hazen and Hurst were together again this week and Hurst said fate has brought the trio together multiple times throughout the years.

Hazen and Hurst were together again this week and Hurst said fate has brought the trio together multiple times throughout the years.

“When we graduated, that summer we volunteered to have our name put at the front of the draft list,” Hurst said. “Yukio was incarcerated for years but still volunteered to serve his country.”

There was a lot of prejudice towards Japanese folks, but Yukio is committed to peace, honor and nurturing relations with other people. You may hear others talk about the camps, but he was there, and he is part of a shrinking group of people.”

Shimomura presented his life to the audience, including the two and a half years he spent in an internment camp in Topaz, Utah and Tanforan in California.

“I want all the students to stand up,” Shimomura told the audience.

“Turn around,” He said.

Shimomura had the students raise and lower their hands and sit down.

“That was only a few seconds that I was in control of your actions, but that is only a minute experience compared to what my family went through for over two years,” Shimomura said.

He said that the residents of the internment camps were told what to do, when to do it and how to do it. Shimomura’s father, mother, grandmother, aunts, uncle and two brothers were all imprisoned in the camp.

Shimomura has been married for over 60 years with children and grandchildren but said he still remembers his time at Tanforan and Topaz.

“Tanforan was a race track in San Bruno, California that was already fenced in,” Shimomura said. “They just had to put up gun towers and barracks and was able to load us in.”

Shimomura and thousands of Americans left were forced from their homes in May 1942 after Executive Order 9066.

“They modified horse stables for living quarters and people stunk,” Shimomura said. “There was no privacy and our mattresses were filled with hay.”

Shimomura was relocated to Topaz, thousands of miles away from his home.

“We said the pledge of allegiance every day and we had flag ceremonies,” Shimomura said. “We all wore the same clothes. This helped to take away our identities”

Shimomura shared one of Dr. Seuss’ propaganda claiming Japanese-Americans were terrorists.

“He was a starving artist, that’s my excuse for him,” Shimomura said. “But I don’t buy Dr. Seuss books anymore nor do I read them to my grandchildren.”

In the 40’s, Utah and Idaho were short on laborers so some of individuals in the camps could work and harvest food. Shimomura said that the showers and toilets were lined up with no privacy.

“I share my story to show that this is real, it happened,” Shimomura said. “I learned that in a panic situation the constitution is put aside and it’s still happening today.”

Shimomura said that what his family experienced was “nowhere near what the internment camps were like in World War I.”

He said, “It was nowhere near how the African slaves were treated when they were brought to this country. It was nowhere near the way we treated the indigenous people of this land.”

Shimomura said he uses a “lowercase ‘c’ for concentration camps” because these other groups had harder experiences.

“We only had to endure for two and a half years,” Shimomura said. “I’m especially concerned about the young people incarcerated at the border right now. It’s not right. I want to tell the administration and congress to get their act together.”

—erickwood97@gmail.com

@GrahamWoodMedia