Column: How we feel, and what we learn

Sometimes when my music library is on shuffle, the perfect song plays. I might be walking to class, or driving home, or getting ready in the morning. But regardless of what it is I’m doing, there’s usually something that I’m feeling – even if it’s unrelated to the task at hand – and I find some relief when something appeals to that feeling. Psychologists and researchers have long acknowledged these invisible realms we live in as a standard feature of our humanity, but how does the fluidity of these social and emotional states fit in the college classroom?

A 2013 report released by the Collaborative for Academic, Social, and Emotional Learning, or CASEL, identifies social and emotional learning as “the process through which students and adults acquire and effectively apply the knowledge, attitudes, and skills necessary to understand and manage emotions, set and achieve positive goals, feel and show empathy for others, establish and maintain positive relationships, and make responsible decisions.”

In short, SEL is how we learn about ourselves and how we apply that subsequent understanding. This ranges from identifying what we’re feeling and why, to articulating those feelings in a positive and constructive way, to being able to hold a civil and respectful conversation with someone we disagree with.

For K-12 educators, social and emotional learning has been a facet of curriculum often crucial to their classrooms for years. Programs like Matthew Henson Elementary’s PATHS exist nationwide, fueled by research that identifies SEL as a key element in preventing prolonged mental health problems later in adult life. But recently, there has been considerable reflection on how these tools might be transposed into higher education.

In June of 2017, stakeholders, scholars, and policymakers from 12 countries gathered at the Educational Testing Service’s Chauncey Conference Center to discuss the applicability of SEL in post-secondary classroom environments at the “Springboard for Success: How Social and Emotional Learning Helps Students in Getting to, Through and Beyond College.” An inspiring amount of conversation at the gathering concerned what has worked and what hasn’t in the classroom, focusing on how emotional and social worlds require a transient approach.

It’s much easier for educators to talk about what has worked and what hasn’t than to use psychological studies to paint university students with a broad stroke and call it a day because of the individuality inherent to our emotional lives. What we feel and why we feel it is deeply personal, no matter how many studies might argue that a neuron is a neuron is a neuron.

We don’t – and arguably can’t – unshoulder these realms before entering the classroom.

Many cases have been made for compartmentalization as a sustainable approach to some semblance of a work-life balance, and not necessarily wrongfully. It’s crucial to structure out your week, setting aside time for each thing you know needs to get done. This way, you can “open and close the door” on what you’re working on, minimizing how overwhelmed you might get if you’ve got a lot on your plate.

But compartmentalizing the concepts we learn in class, shutting them away from the music we listen to, the hikes we go on, the friends we keep close, might not be as sustainable a practice.

I know I’ve had plenty of friends that have had a hard time studying for an exam because of a recent break-up or because they are in contentious relationships with their parents that then bleeds over into how much they’re able to focus in class. Maybe it’s hard to argue that a subject like organic chemistry or business economics has elements that anchor it within our emotional or relational lives, but German chemist August Kekulé – among other ancient scholars – would probably disagree.

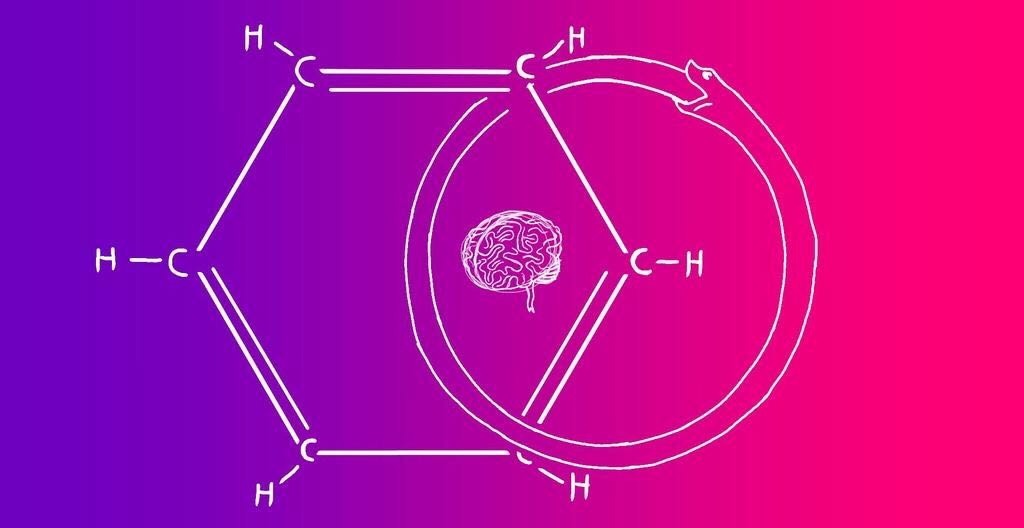

It was only after a vision of the ouroboros – the snake devouring its tail – that Kekulé determined the molecular structure for benzene, similarly cyclical in structure, and his eureka moment has a strong implication for our student experiences.

Regardless of whether you believe Kekulé truly had a vision, alchemical symbolism represents the existence of a realm that brings forth epiphany and understanding alongside lived experience and emotion. By combining the mystery of existence with scientific rigor, he made a largely academic discovery. This represents a large element of SEL approaches.

A research brief released by the National Commission on Social, Emotional, & Academic Development at The Aspen Institute in 2017 acknowledges that a cornerstone of their argument for SEL hinges on the understanding that the “major domains of human development – social, emotional, cognitive, linguistic, academic – are deeply intertwined in the brain and in behavior.” Their brief focuses on the reality that “each carries aspects of the other,” and no one part can be fully isolated from the rest.

So, when we enter the classroom, we carry with us our personal experiences. When we watch a movie or read a short story, the things we learn in the classroom — the terms and concepts and ideas — are still with us.

There’s no way for every teacher, professor, administrator, or advisor to cater to every individual student within some of the broad sweeps their jobs require them to make. Just imagine the professor of your early-morning lecture course attempting to speak individually with all sixty or so of you in one class period. It’s simply not feasible.

Maybe all it would take to recognize opportunities for social and emotional learning in the college classroom is finding a film or novel or painting that relates to the course concepts. Or maybe it’s as simple as finding the symbology of ancient alchemy in the chem lab.