Hook them with humor

Frida Kahlo, one of the founding members of the Guerrilla Girls, presented on Thursday, Nov. 10 as a speaker at the Caine College of the Arts Hashimoto Communication Arts Seminar.

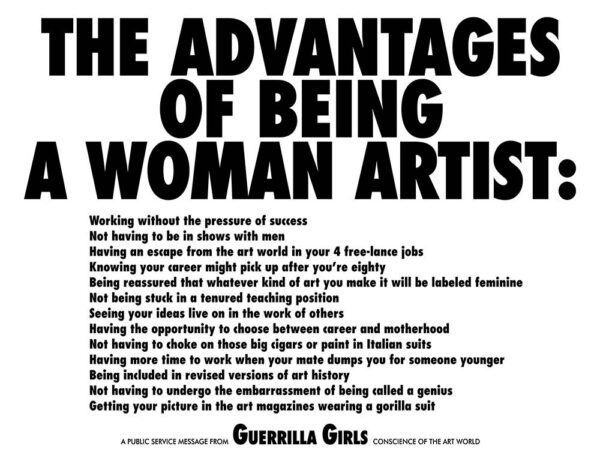

Established in 1985, the Guerrilla Girls are anonymous artist activists who, according to their mission statement, “use disruptive headlines, outrageous visuals and killer statistics to expose gender and ethnic bias and corruption in art, film, politics and pop culture.”

Each member claims anonymity and goes by a pseudonym of a dead female artist. The group believes in “an intersectional feminism that fights for human rights for all people.”

Their art has been featured around the world and continues to be fully accessible to the public. USU Special Collections and Archives owns the Guerrilla Girls’ portfolio of work from 1985 to 2012.

Kahlo was interviewed by Maya Mackinnon, the lifestyles editor at the Utah Statesman, on Nov. 11.

“Your publication is called the Statesman,” Kahlo said. “Why can’t it be called the Stateswoman?”

“Ironic,” Mackinnon said. “Our editorial board is 85% female members.”

“You should change the name,” Kahlo said.

The Guerrilla Girls have visited Utah four times and spoken at USU twice. You said USU was one of the first universities to believe in your work. This begs the question of how the connection was made and why?

Kahlo: “Somebody here likes us, a number of people. Many here must like us. We have never been to Nevada, we’ve been to Wyoming once, never Montana, we have been to Idaho twice. So there’s just something in Utah — there must be forces in Utah and people who are interested in our message.”

Your main focus has been on the art world and many times on museums. Your work is in the street, but your outreach is mostly at universities and colleges. What is the significance of this?

Kahlo: “We are chasing after the meaning of all these invitations. I think what it is, is from the very beginning, we have been producing knowledge, information about the art world. I think educational institutions are the most curious. They embraced us early on and within a year of being formed, we got invitations to talk at colleges. Museums were a little bit slower — I think they had to see there was interest in what we were doing. But it’s also important for us to talk to young students and to see how education is changing, how thinking is changing. We started in 1985. There was no such thing as socially conscious art programs; everyone was trying to be a rich and famous painter or sculptor. And there we were, criticizing the art world that they all wanted to be a part of. So it was a little confusing to students. We were also, in a way, examining art history in a new way, and museum structure and institutions in a new way. Universities are curious about that.”

What role has the internet played in the evolution of your work?

Kahlo: “It has been kind of critical because when we first started, we were putting posters up on the street. Poster by poster by poster. We couldn’t be everywhere; we could only target a certain area. Oftentimes by morning, someone would have posted them over. When the internet came along, we realized that was the perfect way to communicate with people everywhere. It doesn’t have to be a physical object, it doesn’t have to be in a single place. All of a sudden, we started to get letters from women all over the world. Somehow our work had come to their attention. Early on it was because we xeroxed our work and let people reproduce it. But when the internet came along, it was just this great way — exponential way — of increasing our exposure in the world.”

You have seen success. How does almost 40 years of work inform the work you do today? Is there a heightened sense of urgency?

Kahlo: “Any kind of struggle for human rights, sometimes it’s two steps forward, one step back; one step forward, two steps back. It’s never an even ride. The conditions change all the time too. When we first started out, we were interested in promoting diversity inside the art world, and we thought museums and galleries should really show art that looks like the culture we are part of when we realized that there were structural problems in the art world that made that complicated. Museums, for example, in the United States are not very democratic institutions. They are run by rich people. It is hard for the map to represent rich people’s values as opposed to everyone’s values. The deeper we got into examining all the components of bias, it got more and more elaborate, more deep. We have been following that — why women and artists of color don’t get shown in galleries, why women don’t get shown in museums, why they don’t get mentioned in art history books. There’s a kind of thread to all that. Things are changing now because I think everyone realizes history has to be diverse. But it is hard to change the economic mechanism of that. The art world is really based on winners and losers — there are few winners and a lot of losers. You can’t let winners write history. It has to be written by everyone. History is never fixed. We are always finding something new and interesting about the past that helps you understand your own time better.”

What does the midterm election say about feminism today?

Kahlo: “It means we have a lot of work to do, and that we also have a lot of support. The political establishment, in particular the Supreme Court, does not necessarily represent the will of the people. We really have to work on that. I am encouraged because there wasn’t the overwhelming victory for mean-spirited politicians that everyone was predicting. I am hopeful, but there is a scary tendency in the world to want simple answers to questions and elect people to office who are more interested in a strong man to make things happen faster than democratic leaders. But democracy is messy and requires people to discuss things. It is easier to be authoritarian. Too many people are looking for quick fast answers to complex problems. I am hoping that might change.”

If feminism was a food, what would it be?

Kahlo: “Whatever it was, it would be something very nutritious coated in chocolate. Chocolate-covered peanut butter, that’s the one.”

Was there something in particular you would like to have been asked during your presentation at USU?

Kahlo: “That’s a really good thing to ask. Nobody asked us how we support ourselves. It is something I am proud of because we sort of invented a new way of existing in the art world. The conventional goal of many artists is to get out and sell their work for a lot of money and get famous and sell their work for even more money.

Guerrilla Girls

Guerrilla Girls Courtesy guerrillagirls.com

To us, that puts all of the resources at the top and none at the bottom. So, we have always decided that we don’t want our work to be precious, single objects that can be owned and controlled by individual collectors. For 30 bucks, you can have the same poster that belongs to the collection of museums. We sell merchandise, we do talks like this, we do small commissions for museums. We earn our money in really different ways than most artists do, which is selling it to art collectors. We really would rather have our poster hanging in every college dorm room than over the couch of some billionaire art collector. Every museum in the world could own a portfolio of our work.”

To see their work and learn more, visit their website at guerrillagirls.com.