No balls doesn’t mean no guts

The sound of rolling wheels rumbles down a wooden halfpipe as Addie Fitgerald and Addy Ashcroft practice their pumping.

Their goal is to be able to drop in, a scary task for the 9- and 11-year-old skaters. But wearing glittery helmets, the two girls are fully padded.

The halfpipe’s owner, Miley Larson, watches and cheers them on, offering tips and helping when they fall off their boards.

In the summer of 2021, an all-girls skate club called No Balls Skate was created. The club meets in the Logan skatepark on Tuesdays at 5 p.m. and at the Smithfield skatepark on Saturdays at 10:30 a.m.

Its purpose was to give girls of all ages and skill levels a female-friendly space to learn how to skateboard. Based in Cache County, the group travels between Smithfield, Logan, Ogden and Salt Lake.

This Saturday morning is a rainy one, and a group of about seven skaters find bliss at a ramp inside a warehouse storage unit in Smithfield.

Larson’s family rents the storage unit to store the halfpipe. The 19-year-old is the only girl skater in her family and is the face of the skate club.

There is a gender imbalance when it comes to skateboarding, making it difficult for girls to feel comfortable or welcomed in joining in.

“It’s a very male space,” said Michala Zilkey, a member of No Balls. “Historically, there are areas that have been gendered and a lot of people are afraid to go, like weightlifting at a gym, because they view that as a masculine space and they don’t want to go. The skatepark is very similar. There are gendered rules about who has the right to be in each other’s space.”

Zilkey began skating this summer at age 24. During a break from track, she decided to finally indulge in her urge to go skateboarding.

On a warm August morning, Zilkey makes herself coffee, jumps on her cruiser and gets her mind off of grad school.

Solo trips to the skate park brought her good vibes, but with nobody to skate with, there’s nobody to learn from.

Then she heard about No Balls. Her board was only made for riding around, so Marly Guevara lent her a trick board.

“I was like, this is the best time of my life,” said Zilkey. “I want to do tricks, I want to be hardcore.”

She went to Directive Boardshop in Logan the next day to get a new setup. She went back to the park with her new board and was headed on her route when a male skater crossed her path for a rail.

Expecting Zilkey to move, he kept going. Instead of landing his trick, he landed on her ankle.

Her now-broken ankle keeps her off her board and relying on a medical scooter to get around.

She still shows up to the club for the community, and brings along a friend’s younger sister who is getting into skating.

Young girls make up a large portion of the club. Girls as young as 8 come to learn from Larson and Guevara. Guevara also began skating at age 8, but wasn’t taken too seriously by her dad and brothers who are life-long skaters.

Focusing on soccer kept Guevara away from the dangers of skating injuries until she decided she wanted to become a more serious skater.

“My brother started when he was 5. He’s 8 now and he’s better than me,” Guevara said. “So, I saw that and I was like, ‘Oh my gosh I can do this. I want to skate with my family.’”

She sent her dad in to get her deck. Because skate-shop workers are primarily males, it can be an intimidating environment.

This inspired Guevara to get a job at Directive, doubling the amount of women working there.

Larson shares these feelings. When she goes to skate shops, workers question if she knows what she’s doing. They ask, “Are you sure those are the wheels you want? They’re pretty fast.”

“You kind of have to prove yourself,” Guevara explained. “When girls go to skateparks, it takes a few good tricks to show we’re not here to watch, we’re here to skate.”

The group traveled to Salt Lake City to skate on a Saturday evening. The bowl was full of boys irritated at the group for taking up space. That was until they realized the girls were there to skate, and they were good.

The absence of the intimidating male gaze is what makes skate club feel safe — until recently.

The last few weeks, boys have been showing up to the halfpipe in Smithfield. Miley receives messages on the club’s Instagram asking if they can come.

“I don’t want to exclude them,” Guevara said. “The whole point of the club is to make people feel included. If they’re chill, they can hang.”

The boys aren’t always chill, and take over the ramp and the halfpipe — throwing tricks and dominating the space.

Original club members wait off to the sides with their boards, trying to gather the courage to show newcomers their skills.

“I thought this was supposed to be girls only,” Fitgerald said.

It’s a widespread idea in this group that creating a space to prioritize women is important.

Zilkey finds it surprising that in such a liberated space made up of a more alternative crowd, there are still “really hegemonic rules.”

The ruling view in skateboarding is that girls can’t hang, they’re not tough enough.

A recent increase in representation has helped battle these generalizations. Female skateboarders in the 2020 Summer Games were as young as 13.

Seeing Olympians pave the way inspires beginners to find more roads to travel. The few women in the media inspire others, young and old.

Zilkey talks about Paige Tobin, a six-year-old girl who nails big tricks. She’s skated with Tony Hawk, and proves age and gender don’t matter if you have courage to commit.

“The skatepark can be a very intimidating place, especially for beginner skaters,” Zilkey said. “We have a desire to preserve our face, and it hurts our ego when we go out and suck.”

Many of the girls in the club are involved in other activities deemed to be male spaces. They play sports, rock climb and push against society’s expectations in order to do things they really enjoy.

Even in female-created and female-oriented spaces, men are exploiting the creed of inclusivity by taking more than their fair share of space. They assume girls will move over, and when they don’t, ankles break.

But glass ceilings do, too.

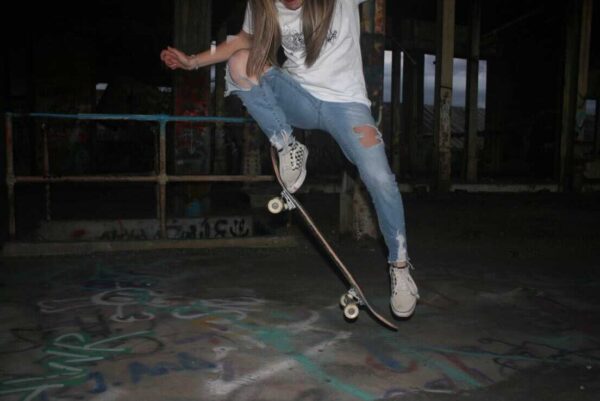

Photos submitted by No Balls Skate.