Opinion: Venezuelan crisis: another opportunity for U.S. to play police

The Trump administration recently announced that Venezuelan President Nicolás Maduro is wanted in the U.S. on counts of narcoterrorism, money laundering and corruption. These accusations come in the wake of increased sanctions on the Venezuelan government to pressure the removal of Maduro from office. However necessary these actions, the United States’ politicization of the Venezuelan crisis serves as a crude example of U.S. global imperialism.

Since his election in 2018, Maduro has enjoyed an infamous reputation at home and abroad. While the election results were considered illegitimate — many Venezuelans protested for Maduro to step down in order to hold a re-election — international intervention happened only after calls from Venezuela’s U.S.-friendly opposition leader Juan Guaidó.

When Maduro took office, he took control of the National Assembly — previously headed by Guaidó. Since being pushed out of office, Guaidó has conducted international tours to gain traction for his campaign to unseat Maduro as interim president but is fully aware that his largest obstacle is the unyielding loyalty of Venezuelan military officials. Incentivizing high-ranking officers to reassess their loyalties is considered by many to be the key to unseating the autocrat.

Narcoterrorism charges and a $15 million reward for insider information were considered steps toward what Michael Camilleri of the Los Angeles Times identified as “undercutting Maduro’s legitimacy and eroding the cohesion of his collaborators.” However, shortly after these charges were announced, the U.S. also released a plan to instate a temporary “Council of State” that would act as a transitional government capable of holding a free election. While mirroring a plan released by Guaidó shortly before, the United States’ approach additionally calls for both Maduro and Guaidó to relinquish their claims to leadership. The plan did not prevent Guaidó from running for office, and Maduro, predictably, rejected it.

Increased sanctions on Venezuela in the last year have made clear the U.S.’ intentions to isolate the Maduro regime but also highlight the fog of imperialism that still lingers over our political framework. While participating United Nations countries came together last year to invoke the Inter-American Treaty of Reciprocal Assistance (TIAR), which allowed a number of countries to enact economic sanctions or bar Venezuelan officials entry, the questionable control the U.S. exercises over UN movements should raise concerns.

The United States is currently the largest financial donor to the UN, “contributing more than $10 billion in 2017, roughly one fifth of the body’s collective budget,” according to a 2019 report by the Council on Foreign Affairs. While the U.S. disproportionately funds an organization built as an international check on global leadership, it has held a unique impunity for human rights abuses while simultaneously criticizing others for doing the same.

Former U.N. High Commissioner for Human Rights Navi Pillay went so far as to call the failure to close Guantanamo Bay – the detention center used by the U.S. during its “so-called ‘global war on terror’” – a “clear breach of international law.” Despite the density of academic literature concerning human rights violations committed within the confines of the prison, the U.S. government has continued to hold detainees indefinitely and without the hope of due process, a practice the deputy director of the U.S. Program at Human Rights Watch, Laura Pitter, said “poses a far greater security threat to the US than the release of any one detainee.”

This hypocrisy does not diminish the egregious nature of the Maduro regime. I’m glad that the U.S. has joined with other countries to support a shift to a sustainable Venezuelan democracy. However, I believe that our efforts to lead this movement can only appear less formidable in the wake of long-standing rights violations committed by the United States itself. Lack of accountability may be due to the excessive influence the U.S. wields on the international stage — an influence that may be waning in the wake of the coronavirus pandemic — and should be considered as we attempt to move forward in securing just governments in other nations. Perhaps we should concern ourselves with restructuring our own accountability measures before policing others.

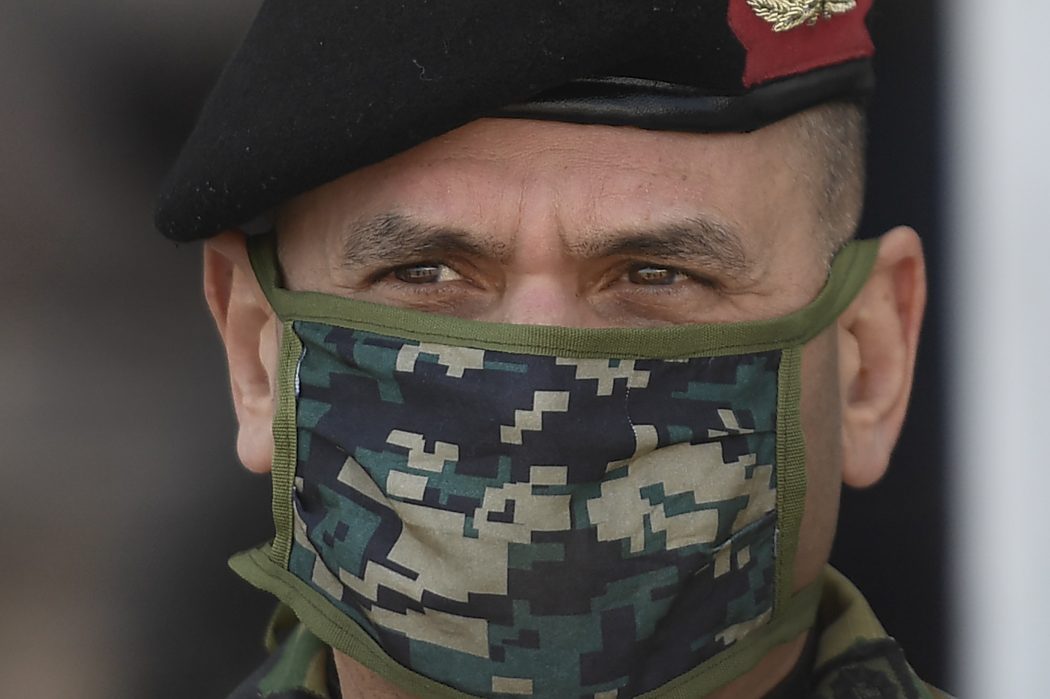

Featured image courtesy of AP Photo/Matias Delacroix