Protecting the wilderness: students play a role in preserving the Cache National Forest

Utah.com claims Logan Canyon is “the scenic drive for fall foliage fanatics.” If one is lucky, they might catch a fish in the Logan River or see a family of elk amongst the changing leaves. Logan Canyon, and the wildlife inside it, puts on an autumnal show for Cache Valley residents. But what is being done to protect it?

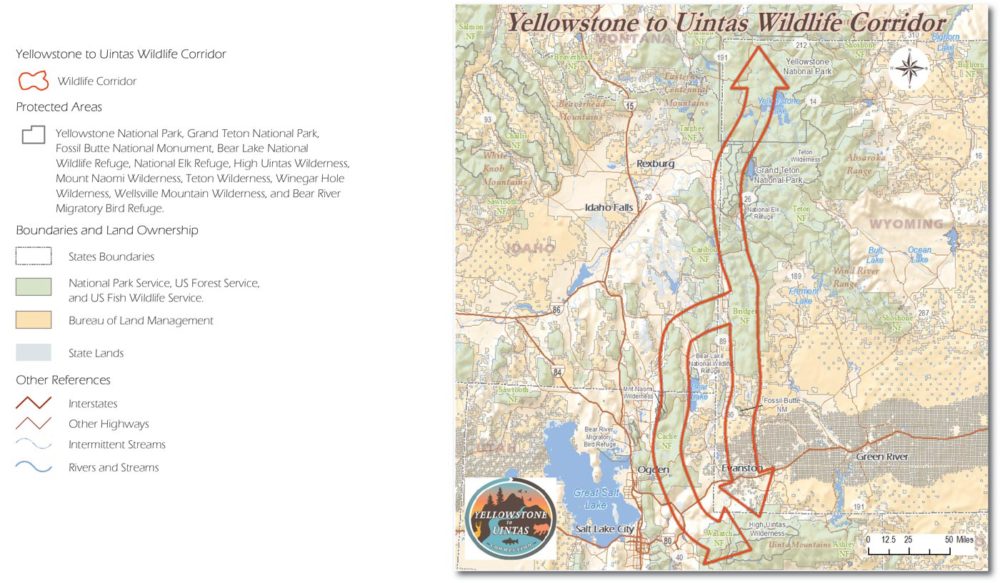

Yellowstone to Uintas Connection (Y2U) is a non-profit organization created to protect and maintain the wildlife corridor, or passageway, that connects Yellowstone to the Uinta Mountains. This length of ecosystem runs through Wyoming, Idaho and Utah, and includes the Wasatch-Cache National Forest. Y2U aims to provide a connected network of habitats to allow for the safe movement of wildlife through this corridor, a term coined “wildlife connectivity.”

According to Jason Christensen, the director of Y2U, this corridor is a major passageway for deer, elk, wolves, and other animals that are beginning to experience negative effects from being isolated in Yellowstone or the Uintas.

“The problem is that we’ve created these islands of conservation, like Yellowstone, the Uintas and the Grand Canyon,” said Jason Christensen, the director of Y2U. “Wildlife populations are now becoming isolated because they aren’t able to safely travel amongst populations. This creates a problem with genetic diversity. We are starting to see inbreeding in the grizzly bears in Yellowstone because there is no genetic diversity through corridor travel.”

Yellowstone to Uintas Connection

Yellowstone to Uintas Connection The Yellowstone to Uintas wildlife corridor runs from Yellowstone National Park to the Uinta mountain range.

Y2U was founded in 2012 by John Carter, a PhD ecologist and Utah State University alumni. After living on a 900-acre wildlife preserve he established in Idaho, Carter realized there wasn’t enough being done in the wildlife corridor connecting the ecosystems of Yellowstone to the Uinta mountains. In addition to restoring the fish and wildlife population in this corridor, part of Y2U’s mission is to educate Cache Valley residents on the importance of habitat connectivity for wildlife.

“We feel like educating the youth is the only way we’re going to save this planet, as it seems like the older people have their minds set on destroying it,” Christensen said. “Part of that education is hiring student interns from USU to give them real field experiences.”

After graduating in conservation and restoration ecology from Utah State University in May, Casey Brucker landed an internship with Y2U. After just one month, she was offered a full-time position as the organization’s ecological technician. Brucker has helped Y2U implement three different projects so far.

“I finished up a project with the Bear River watershed where I was taking water quality samples and checking them for E. coli,” she said. “I was also doing a sage grouse tag project, and I also helped put cameras up in Paris, Idaho where we are doing a predator survey. I’m going to start writing grants and doing advocacy and outreach soon.”

Brucker said it is very fulfilling to work with an up-and-coming environmental organization with a good cause.

“Yellowstone to Uintas combines science with education and advocacy,” she said. “They take the science and make it useful. It’s one thing to write a paper and another thing to actually take action.”

Having Logan Canyon and other places for outdoor recreation near Utah State is a factor many students consider in deciding to enroll in school there, Brucker said. She finds it important to preserve the wildlife and ecosystem of Cache Valley, as it is of great value to its residents.

“All of our education efforts are created with future generations in mind,” Brucker said. “Students at USU may stay here and have their kids grow up here. We have to ask ourselves, ‘What is it going to look like? What can we do to preserve this?’”

With over 20 current projects, Y2U is constantly seeking community members and students to volunteer, help with projects, and perform a crucial role in the preserving of the lands we call home. Projects listed on the organization’s website include working with off-highway vehicles, forest management, watersheds, grazing, trapping, mining, and oil drilling.

“We have quite a few young people who are starting to work for us, and even just volunteer,” said Logan Christian, a USU graduate and the outreach director for Y2U. “Volunteers are what make it work. They are what make Y2U happen. We are working together to make Logan a better place for people and wildlife.”

Christian wants students to go outdoors, get connected, and establish a relationship with their public lands. Volunteering with Y2U is one way students can make a difference.

“We all have access to these places, but they are getting degraded by timber harvesting or grazing. These are places we could be recreating if people knew more about them,” he said. “We are constantly looking for students to get involved, regardless of their field. We need people to be involved because everyone has got a piece in this.”

Y2U works with issues of logging and extraction on public lands, as species like lynx and wolves require an unfragmented habitat to thrive. But the lower portion of the Yellowstone to Uintas corridor is largely private land, which creates a more complicated problem for Y2U in trying to create wildlife connectivity.

“One of our biggest projects right now is building wildlife-friendly fencing on private ground,” Christensen said. “The top wire is barbless, and there’s 12 inches until the next wire. This keeps the deer from getting caught in it and there’s enough room for foxes to go underneath. The fencing gets lowered to the ground during the winter so wildlife can pass over it.”

At 14 thousand dollars a mile, most ranchers and private land owners can’t afford to implement it, Christensen said. By identifying choke points and migration routes and putting in miles of wildlife-friendly fencing, Y2U creates a partnership with private landowners so they can work together toward a common goal.

“We are really trying to change the stigma about communication with environmental groups,” Christensen said. “Most environmental groups are all about fighting, usually through litigation, against the forest service, the BLM, and the ranching community. We are trying to figure out ways to come up with solutions without litigation, working together with agencies that are very much understaffed and underfunded and can’t manage what they are charged with managing.”

Kyle Todecheene

Kyle Todecheene Once the organization has its foot in the door with private landowners, Y2U members can start talking about how to preserve the land for recreation without coming off as threatening.

“We are trying to be a face of conservation they actually trust,” Christian said. “We are there to help them and provide them with fencing. We want these landowners to reach out to us with questions or ideas and no longer have it be conservationists versus private landowners. We would love if volunteers even wanted to come out and help us install the fencing.”

Christian said the best part of working on a local, regional issue is the difference he is making in the outdoor areas he has played in since he moved to Cache Valley at 3 years old.

“I got involved with Y2U after finding out I could take the skills I learned in the College of Natural Resources and turn that into protecting the placed I ski in, hike through, and camp in,” Christian said. “If you get involved as a USU student, you are bettering the places where you can then go recreate. You’re helping protect wildlife you can drive up the canyon and view with your binoculars.”

Individuals who want to be involved with Yellowstone to Uintas Connection can join the organization’s email list or sign up to volunteer at yellowstoneuintas.org. All projects are open for students to help.

— mekenna.malan@gmail.com

@kennamalan