Remote Sensing and GIS Laboratory keeps a bird’s-eye view on Utah

USU’s Remote Sensing and GIS Laboratory has an aerial perspective on the changes happening to Utah’s physical terrain, from the state’s mountainous peaks to the Great Salt Lake.

Remote sensing is the process of detecting the features of the ground without making contact. This is typically accomplished through the use of drones or satellites. Geographic information systems, or GIS, are the tools used to analyze and present geospatial data.

Doug Ramsey, director of the laboratory and professor for wildland resources, founded the lab and began using it to provide assistance to other faculty who didn’t have a geospatial background.

Ramsey is an expert in remote sensing technologies and said they have been evolving for decades.

“It really started in World War I when we started taking aerial photographs,” Ramsey said. “Ever since World War II, they’ve been taking aerial photographs of the whole country every 10 to 20 years. Now they take aerial imagery of the whole country every two years.”

Satellites in orbit can take an image of the country twice a day. Technology like this has allowed Ramsey and his team to take on large-scale projects.

“The biggest thing we’ve done was map land cover across the whole state,” Ramsey said. “We have such a fairly long history — 40 to 50 years — we can get a pretty good idea of how landscapes are shifting from one cover type to another cover type.”

Remote sensing imagery is commonly used to compare certain areas of land over different periods of time to track water level changes, city growth, deforestation and more.

An example Ramsey worked on was how the amount of cheatgrass, an invasive weed, fluctuates between seasons.

Christopher McGinty is a graduate student who works as the manager of the lab.

“We’ve had a ton of opportunities to do invasive species mapping,” McGinty said. “It’s been so gratifying to be able to take some of this technology and translate it into something that anyone can go and use.”

According to McGinty, he works on projects with senior citizens to teach them about drones and remote sensing.

“We’ve been able to teach them how to fly drones. We were able to talk to them about remote sensing, and they absolutely love it,” McGinty said. “Geospatial technologies can get anyone excited.”

Satellites, drones and manned aircraft are utilized in remote sensing for different needs. There are currently hundreds of satellites orbiting the planet, and many of them, such as the Landsat satellites, are used for Earth observation.

“Satellites are good for large landscape studies,” Ramsey said. “Drones are good for small landscape studies. Piloted aircraft are good for medium-scale studies.”

Over the years, Ramsey has taught dozens of graduate students in his lab, many of whom went on to use their skills professionally.

“We work on federal contracts, we’ve worked on state agency contracts,” McGinty said. “We had the opportunity to work on so many different projects, and I think that’s what I really loved about it, was we had the opportunity to dabble in urban growth and development, rangeland resources, forestry.”

McGinty said he has recently focused on water mapping, which has given him the chance to work with Salt Lake City Public Utilities to help with their conservation plan of the Great Salt Lake.

“People just want to have green grass,” McGinty said. “We live in a desert, so that doesn’t make a lot of sense. But if we can help them see what they should be using on their landscapes versus what they are, we can put it in a couple of different frames. We can frame it as being environmentally conscious and saving water, but you can also frame it as saving money.”

Chris Garrard, a programming analyst at USU, builds GIS tools to help analyze data. She worked for the Forest Service to write a program that could analyze carbon sequestration.

“I’m looking at everything like, ‘How can we automate this function, or how can we build some cool app for it,’” Garrard said. “I’m learning new stuff every day, which is why I like this job.”

While teaching graduate students, Garrard said she enjoyed helping them how to automate things for research.

“I’d have students saying, ‘You just saved me a year’s worth of work by what I just learned in one hour in class today,’” Garrard said.

Programming and coding are a large factor in GIS, and they can make the experience easier to understand.

“If you want to get into remote sensing and GIS, learn some coding,” Garrard said. “I think anyone who wants to get into that stuff and do well at it has to know some of the tech side of it.”

Remote sensing is a relatively new field, and the tools change frequently.

“This thing changes on a yearly basis,” Ramsey said. “It’s a dynamic thing. You got to keep up, or else you kind of fall behind pretty quick.”

According to Ramsey, remote sensing technologies affect most people daily, whether they realize it or not.

“It’s basically driving everything,” Ramsey said. “Everything you do in life is somehow linked to GIS, which uses remote sensing as a primary data input. So even if you’re just using Google Maps to tell your car to go from point A to point B, you’re using a GIS.”

GIS commonly uses data collected by remote sensing.

“We see photos from drones, we see photos from spy satellites that they put on the news, and that’s all remote sensing,” McGinty said. “Remote sensing, GIS and geospatial technology is becoming ubiquitous across our culture.”

McGinty said when he taught GIS, he barely had to fail any students because it was so easy for them to apply the data to hiking, skiing or other activities they enjoy in their personal lives.

“From that data, you can extract roads, extract rivers — you can extract a lot of different features,” Ramsey said.

These technologies have allowed Ramsey to observe changes in the Great Salt Lake over time, which is important information in making policy decisions about environmental protection.

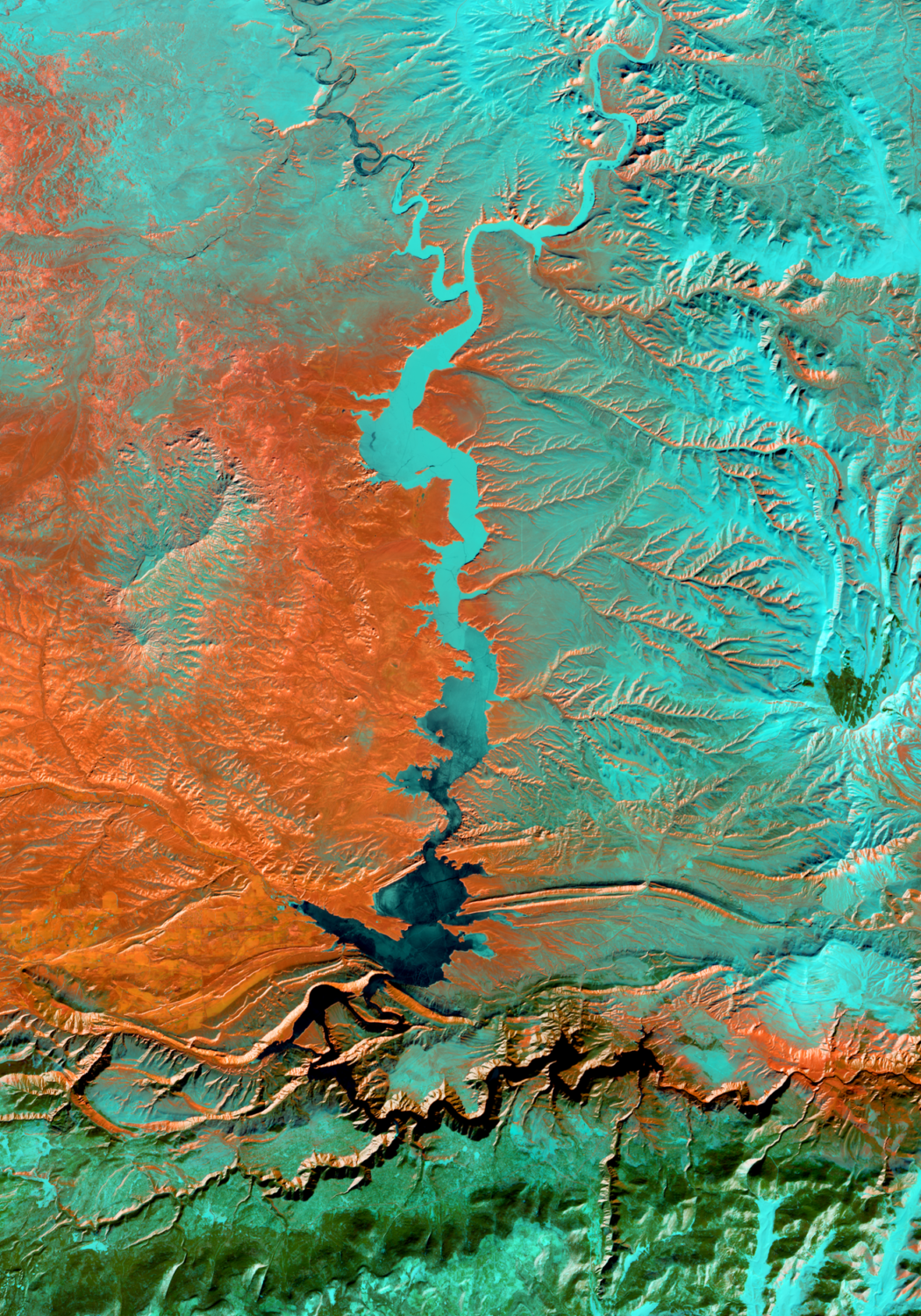

According to Ramsey, some remote sensing imagery produces depictions that cannot be seen from the ground without satellite technology.

“We can take any wavelength of the spectrum that’s collected by the satellite and assign it to the red, green and blue,” Ramsey said. “So you’re looking at things that you really can’t see with the naked eye in the natural world.”