Sexual assault cases on the rise

Twice as many sexual assault offenses were reported in 2012 than in 2011, according to the Crime Awareness and Campus and Fire Safety Report.

Sexual Assault and Anti-Violence Information program coordinator Jenny Erazo said it’s hard to say why the statistic spiked.

“Sexual assault is one of the most underreported crimes,” Erazo said. “Maybe the circumstances were just right and people reported it.”

Captain Steve Milne of the USU Police Department said there are many reasons why people are reluctant to report a rape or sexual assault to the police. They might have been drinking and were underage. Maybe they don’t want their parents finding out. It’s a very personal and emotional matter, he said.

He said a victim is sometimes reluctant to report the issue because they personally know their attacker.

“A lot of people’s vision of rape is a stranger that breaks into their apartment and sexually assaults them,” Milne said. “This is a guy they went on a date with.”

According to Milne, more people are willing to go to SAAVI to report the incident than the police. SAAVI works with the survivor to report to the police when a violation occurred.

“None of the confidential or case specific information is shared, just that there was a rape or sexual assault on campus,” Erazo said.

Milne said a lot of survivors struggle with believing it’s their fault, and what a friend says may validate that belief.

Erazo hopes to change the tendency to blame the survivor.

“Our culture is a lot of blaming, and there’s a lot of guilt associated with being a victim of rape or sexual assault,” Erazo said. “If your daughter died in a car accident, people aren’t going to say, ‘That’s her fault for not taking the bus,’ but with rape and sexual assault, that’s what’s happening, and that’s just silly.”

When a rape or sexual assault is reported to the police, the victim is in control. They can report it and request no action be taken, they can request the police make the suspect aware his or her actions are wrong or they can pursue criminal charges, Milne said.

“I’m here to help, but these decisions are yours,” Erazo said. “Come when you feel ready. Please know that we’re here as a resource.”

Erazo said some students detach themselves from the situation and it isn’t until later, when something happens to remind them or they’re in a relationship, when they feel the effects. With others, the emotions are close to the surface.

“Everybody responds to trauma differently,” she said.

Occasionally students will turn to drugs, alcohol or develop eating disorders, but in general, Erazo said she sees people come through it strong.

“I was so impressed by the strength that I saw, and I thought, ‘I can do this, I can help make a change,'” she said.

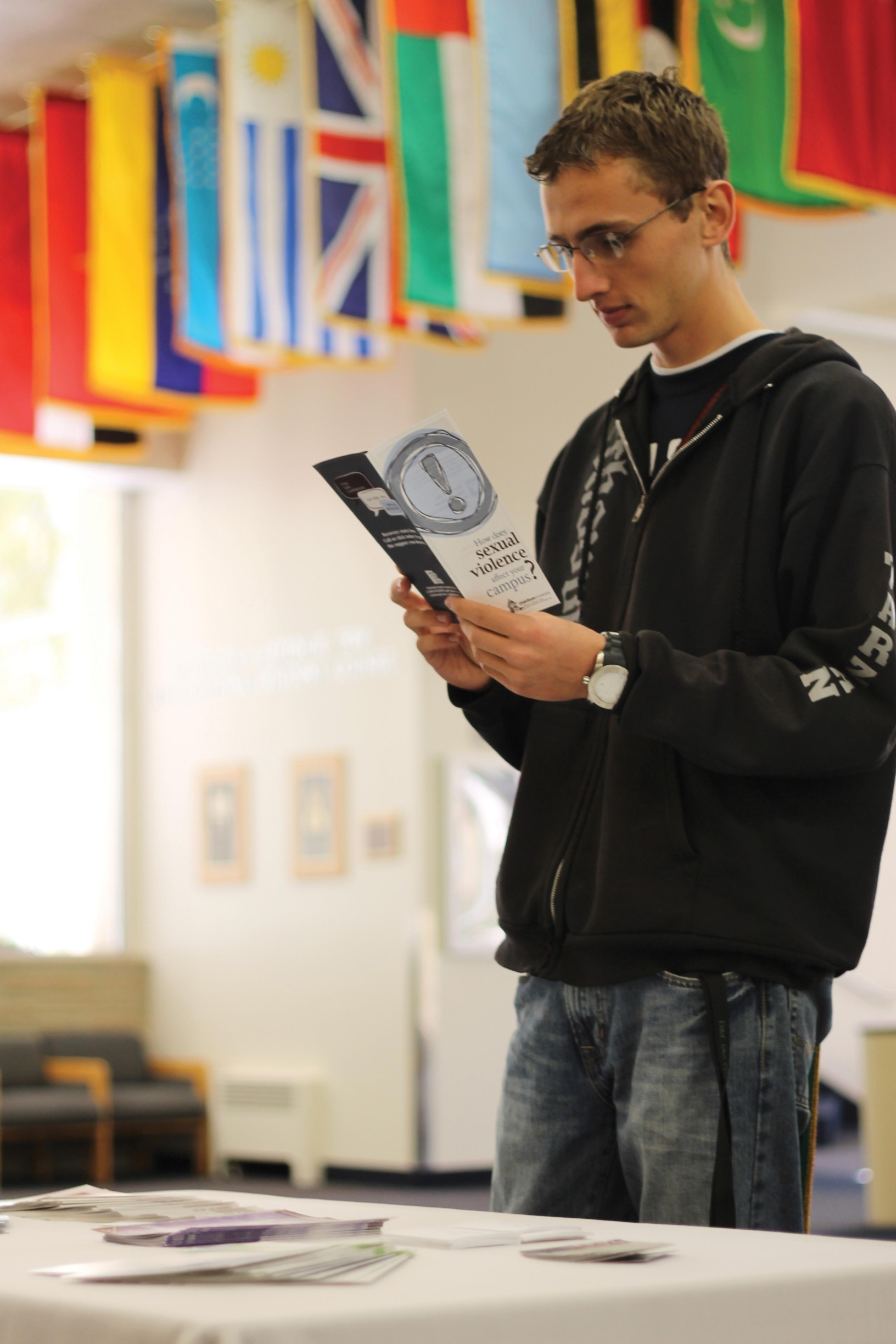

Erazo would like to make students and faculty more aware of SAAVI and what it does.

“I’d like to get in with the advisers, people who work with students directly,” she said.

SAAVI is also working to involve men in a positive way.

“People tend to think that it is just a woman’s issue, but there are so many ways that men can get involved and be positive role models to other guys on how to treat women,” Erazo said.

Another resource on campus is the Rape, Aggression Defense class taught by Joe Huish, the defensive tactics instructor for campus police. It’s a full semester class taught twice a week.

“I teach girls how to fight dirty,” Huish said.

Milne said a good way to stay safe is to set boundaries and tell a person “no.” If someone is in a situation where a person is not listening, get out.

The SAAVI office is in the Student Health and Wellness Center in room 119.

@BurnettMaile