The long term effects of sexism on women in STEM

Anna Fabiszak knew exactly what she wanted to do.

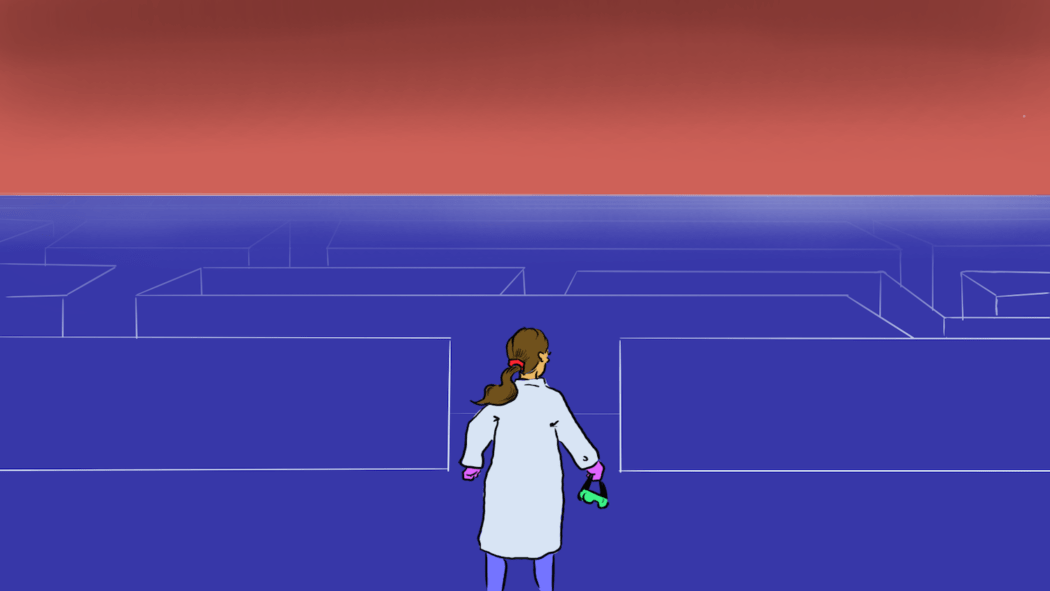

Chemistry had been her favorite class in high school. She’d done well in it, too. She was excited by the ways in which chemicals conspire to create life. And whenever she would picture her future self, it was in a lab coat and goggles.

So when she arrived at Utah State University in 2009, chemistry was the major she wanted to pursue.

By 2010, though, she was majoring in nutrition science. Her love for chemistry had been relegated to a minor.

She’s not alone. Women make up a majority of students at Utah State — but a minority of those earning science, technology, engineering and mathematics degrees. Female professors and students in STEM say it wouldn’t be that way if women were allowed to have the same unearned confidence that so many men have.

Sexism in STEM programs isn’t as prevalent as it used to be. “It seems like the men are very accepting and anxious to work with the women,” explained Vicki Allan, a computer science professor at USU.

So why aren’t more women majoring in STEM programs?

“What happens is if a guy is getting a C, they just go, ‘I don’t care, I love my major and I’m staying in it.’ If a woman is getting a C, they’re going, ‘Oh, everyone told me I couldn’t do this, I guess I can’t,’” Allan said.

According to Allan women often self-select so only the ones who get high grades stay in the program. She believes that women are self-selecting for failure — likely because of what they’ve heard about their chances for success.

That’s what happened to Fabiszak.

“I’m not the best at math,” Fabiszak said. “Math was always my weakest subject.”

“Weak” for Fabiszak meant Bs, not As — and a challenging time passing a test in an introductory college math class that she took in high school.

Math, of course, is an important part of chemistry. And that alone was enough to push Fabiszak into another major.

But as Fabiszak neared the end of her nutrition degree she realized she had made a mistake.

“I remember being at that point in my degree where I was like, ‘I don’t want to be a nutritionist,’” Fabiszak said.

In the fall of 2012, she started taking organic chemistry. “It was always kind of in the back of my mind,” Fabiszak said.

It was like a switch flipped in her brain — she had to switch majors.

Fabiszak immediately scheduled an appointment with her adviser — but was discouraged from making the change, which might have pushed back her graduation date.

According to a study from the Girl Scout Research Institute, 74% of girls in middle school say they are interested in studying STEM subjects.

How many stay in those fields through college? Less than 20%, according to the study.

In 2014, Fabiszak graduated USU with a nutrition science degree and a minor in chemistry. She never used her major.

Unlike Fabiszak, Anastasiia Tkachenko started in STEM and is finishing in STEM. Tkachenko is a Ph.D. student from Russia studying computer science at USU.

Early on in her education, Tkachenko was surrounded by women. In high school, she attended classes with 11 girls and one boy. She learned algebra, biology, chemistry and physics surrounded by female peers. Most of Tkachenko’s teachers were women, and she recalls that they always supported her choice to go into technology-oriented programs.

After ninth grade, students individually choose to either stay in school or continue in a trade school, where they are educated and work in a career sooner. Even though most men in Russia choose to go to a trade school, Tkachenko noticed a steep drop off of women studying with her as she furthered her education.

Tkachenko said that after her undergrad program, she had fewer female friends.

“Most of my classmates just decided to leave education,” she said. As her friends began dropping off, so did Tkachenko’s female professors.

People attribute the gradual decline of women in STEM fields to different things, but Utah State chemistry professor Kimberly Hageman has a hypothesis.

In her own life, Hageman found that female support and representation got her into chemistry. Because her father was a working chemist, Hageman found herself in chemistry labs at a young age.

Watching women in white lab coats performing experiments and working in chemistry labs gave Hageman the confidence to study chemistry in higher education.

“I didn’t necessarily think I could be a professor until I saw that there are women professors,” Hageman said.

As she watched her female classmates drop out of school, Tkachenko noticed a trend that supports Hageman’s hypothesis.

“It seems that they kind of choose between education and family,” she explained.

Vicki Allan is one of the only female computer science professors Tkachenko has. Like Tkachenko, Allan was encouraged to pursue STEM programs.

“My father was actually head of the department at USU in computer science,” Allan said. “He talked my husband into computer science.” Meanwhile, Allan received undergraduate and graduate degrees in mathematics. When it came time to get a job, Allan found herself in a pickle.

“If you were a math teacher, they wanted you to coach football, basketball or track,” Allan said. “The positions were linked.”

There were jobs in computer science, but at first Allan didn’t feel confident that was the right path for her — after all, she only had a minor in that subject, but she ultimately decided to give it a try.

As she taught, she began to realize something.

“I’m really good and love computer science,” Allan said.

At Utah State, Allan says only 12.8% of students in the undergraduate computer science program are women — less than the national average. On top of that, in terms of percentage, Allan said the computer science program has more women leaving the field than men.

“The stereotypes against women in tech start young and are reinforced by parents and peer groups,” Allan said. If young women are not encouraged to pursue tech, they are less likely to do so as they get older.

Freshman year is a formative one. Wide-eyed students are often in a new town, sharing tiny apartments with people they’ve never met and going to classes taught by experts in the field. At parties, new students find themselves meeting hundreds of new faces with one question: What is your major?

“You kind of gauge the reaction,” Allan explained. A woman majoring in elementary education is more likely to be encouraged than the woman majoring in STEM, not because of difficulty levels, but because of stereotypes. Those reactions, Allan says, affect women more than we might think.

Allan wants the stereotypes, statistics and self-selection to change. That change might be slow, but it’s happening.

Over the summers, USU helps run an App Camp for girls and boys in middle school. In the camp, students learn how to develop apps. This year, Allan had an important question that still needs answering.

“If we get females in an all-female class, do they do better?” Allan asked.

To find out, App Camp leaders would need to have enough girls to create an all-female session and a combined male and female session. But in what was perhaps a sign that there is still a lot of work to be done, the female sessions didn’t fill up all summer.

That didn’t prevent the organizers from drawing some important conclusions.

“Basically, what we learned is that young women do not need an all-female space to thrive,” Allan said. “But, what is important is the support of parents in pursuing a non-traditional interest.”

Still, women need to feel supported by their peers and according to Tkachenko, clubs are the way to do that.

“Vicki Allan sent me an invitation to join the Association for Computing Machinery for women,” Tkachenko said. “It was really amazing, just because I didn’t know that actually, computer science provides such a club.”

The club is an organization at USU that promotes computer machinery for women.

Clubs like this help women find support in their STEM majors. Being a part of it is encouraging to Tkachenko.

Fabiszak found her courage and came back to USU in the spring of 2020. She is now studying chemistry.

“We still need more women to feel like they can go into STEM,” Fabiszak said. “A lot of us are gonna open up doors for younger women.”

Last summer, Fabiszak worked in the Hageman lab conducting field studies and lab experiments. She now works as a research technician in the biology department, working in a lab coat with goggles.